Tutorials¶

This set of tutorials is designed to guide the users through the process of encapsulating their stochastic dynamical system into the framework of pyTAMS in order to smoothly leverage the capabilities of rare event techniques.

With the exception of a few example cases shipped with the code, pyTAMS will always require the user to formulate her/his problem in as little as a few dozens of lines of code, to hundreds if the complexity of the model warrants it.

1D double well¶

In this first tutorial, our aim is to implement the 1D double well model already presented at the end of the Theory Section. This model is not provided out-of-the-box in pyTAMS and will be written from scratch.

Background¶

As a reminder, the 1D double well stochastic dynamical system can be described with the following stochastic differential equation:

where \(f(X_t) = - \nabla V(X_t)\) is derived from a symmetric potential:

\(X_t \in \mathbb{R}\) is our Markov process, \(\epsilon\) is the noise scaling parameter and \(dW_t\) a 1D Wiener process. We will use a simple Euler-Maruyama method to advance the system in time.

Getting set up¶

If you haven’t done so yet, let’s get the latest version of pyTAMS installed on your system. In your favorite environment manager, simply use:

pip install pytams

tams_check

The second line check that pyTAMS is effectively installed and should return (with proper version numbers):

== pyTAMS vX.Y.Z :: a rare-event finder tool ==

Now create a new folder for us to work in:

mkdir tams_1d_doublewell

cd tams_1d_doublewell

Writing the forward model¶

Our first task is to implement the SDE provided above in a class that can interact with pyTAMS. As mentioned in the Implementation Section, one needs to wrap all the physics of the stochastic model into an Abstract Base Class (ABC).

To make it easier to start this process from scratch, pyTAMS provides a helper function:

tams_init_model -n doublewell1D

A local doublewell1D.py file is created, with a skeleton of your new doublewell1D

class, inheriting from the pyTAMS required ABC and providing the minimal set of methods (functions)

that are required to run TAMS:

def _init_model(self, m_id: int, params: dict[typing.Any, typing.Any]) -> None:

def _advance(self, step: int, time: float, dt: float, noise: Any, need_end_state: bool) -> float:

def get_current_state(self) -> Any:

def set_current_state(self, state: Any) -> None:

def score(self) -> float:

def make_noise(self) -> Any:

We will now have to properly fill these six functions. Let’s start with _init_model function,

which is called by the superclass initializer and allow to initialize model-specific parameters:

def _init_model(self, m_id: int, params: dict[typing.Any, typing.Any]) -> None:

""" ... """

# Initialize the model state (a single float here)

# We always start at -1.0

self._state = -1.0

# Parse an amplitude factor from the input file

self._epsilon = params.get("model",{}).get("epsilon",0.02)

# Let's initialize the Random Number Generator (RNG) to use around

self._rng = np.random.default_rng()

In this simple model, the model state is a simple float. Note that the state type is

completely up to the user and/or requirements of the model. For instance, if you run an

external program, it might be a path to the program checkpoint file. The above code also

shows how to read-in parameters specified in the input file (see below). Finally, we

initialize a random number generator for subsequent use in the noise generation. This

is not specifically necessary, but it is good practice to control the RNG and we could

pass the model instance ID number m_id, to fix the seed of the RNG and make the runs

reproductible.

Let’s look at the getter and setter of the model state:

def get_current_state(self) -> Any:

""" ... """

return self._state

def set_current_state(self, state: Any) -> None:

""" ... """

self._state = state

These two are pretty straightforward for this simple model. Similarly, the make_noise

function writes:

def make_noise(self) -> Any:

""" ... """

return self._rng.standard_normal(1)[0]

Let’s now dive into the _advance function. We will use a Euler-Maruyama scheme to

update the model state, defining the drift function as another method of the class.

def _drift(self, x: float) -> float:

"""Drift function.

The drift function f = - nabla(V) = x - x^3

Args:

x: the model state

Returns:

The double well drift at the provided state

"""

return x - x**3

def _advance(self,

step: int,

time: float,

dt: float,

noise: Any,

need_end_state: bool

) -> float:

""" ... """

self._state = (

self._state + dt * self._drift(self._state)

+ np.sqrt(2 * dt * self._epsilon) * noise

)

return dt

Note that it is important to use the incoming noise noise and not generate another

noise within the advance function. This is because pyTAMS internally keep track of the

noises provided to the advance function, caching them when the model state is sub-sampled for instance.

Additionally, the advance function must return dt the actual time step size used by the model.

For the current model, this is simply the same as the input parameter dt, but some external

program might have other constraint not allowing the model to run for exactly the provided dt.

Finally, for the score function, we will use the \(\xi\) function mentioned in the Theory Section:

where \(\mathcal{B}\) is at \(X_t = x_b = 1.0\) and \(\mathcal{A}\) is at \(X_t = x_a = -1.0\),

with the later being our initial condition. Implementing this in the score function:

def score(self) -> float:

""" ... """

x_a = -1.0

x_b = 1.0

return (1.0 - np.sqrt((self._state - x_b)**2) / np.sqrt((x_a-x_b)**2))

One last thing we need, is to import the numpy package since we have used it in several places. At the top of your file, with the other imports, add:

import numpy as np

And that is pretty much all you need to have a functioning model class !

Testing the model¶

Before running TAMS, let’s test the model integration within pyTAMS framework by running

a single trajectory. In a separate python file (e.g. test_dw1D.py), copy the following:

from pathlib import Path

import toml

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from pytams.trajectory import Trajectory

from doublewell1D import doublewell1D

if __name__ == "__main__":

# For convenience

fmodel = doublewell1D

# Load the input file

with Path("input.toml").open("r") as f:

input_params = toml.load(f)

# Initialize a trajectory object

traj = Trajectory(0, 1.0, fmodel, input_params)

# Advance the model

traj.advance()

# Plain plot the trajectory score history

plt.plot(traj.get_time_array(), traj.get_score_array())

plt.grid()

plt.show()

Note that when running TAMS directly, the user does not have to load the input file

manually. We also need to initialize an input TOML file input.toml containing the trajectory

and model parameters (see Usage Section for a complete list

of input keys).

[trajectory]

end_time = 10.0

step_size = 0.01

[model]

epsilon = 0.05

We will simulate the random process for 10 time units, with a time step size of 0.01.

Let’s now run the script:

python test_dw1D.py

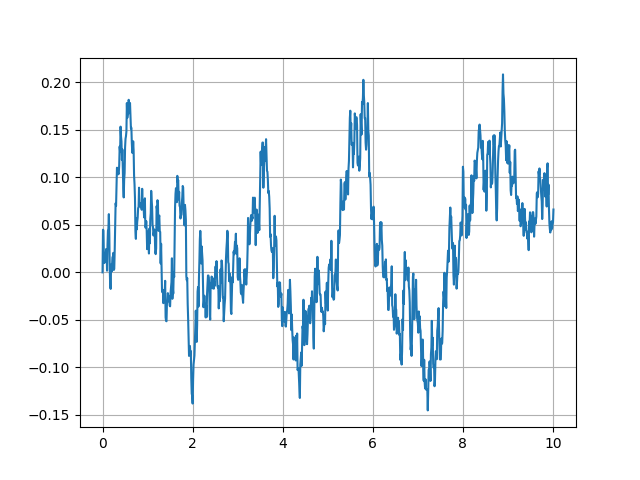

Hopefully, this should produce a graph of the same type as the one below (but with a different trajectory due to randomness).

Figure 7 Score history for a single trajectory of the 1D double well model¶

Feel free to tweak the input parameters to see if you can trigger a transition ! We are all set to run TAMS.

Running TAMS¶

Similarly to the short script we wrote above to run a single trajectory, let

assemble a small script to run TAMS (e.g. in tams_dw1D.py):

from pytams.tams import TAMS

from doublewell1D import doublewell1D

if __name__ == "__main__":

# For convenience

fmodel = doublewell1D

# Initialize the algorithm object

tams = TAMS(fmodel_t=fmodel)

# Run TAMS and report

probability = tams.compute_probability()

print(f"TAMS converged with a transition probability: {probability}")

# Show the envolpe of the ensemble over the course

# of the algorithm

tams._tdb.plot_min_max_span("./doublewell1D_minmax.png")

We also need to update the input file with additional parameters relative to the algorithm parameters:

[tams]

ntrajectories = 50

nsplititer = 500

[trajectory]

end_time = 10.0

step_size = 0.01

targetscore = 0.95

[model]

epsilon = 0.04

[runner]

type = "asyncio"

nworker_init=1

nworker_iter=1

With above input parameters, the TAMS ensemble will contain 50 members and the algorithm will proceed up to a total 500 selection/mutation events. The model is assumed to have transitioned if the score function exceeds \(\xi_b = 0.95\). We will run using the asyncio runner, with a single worker during the initial ensemble generation and the iterarion process. We have reduced the noise level to \(\epsilon = 0.04\).

Let’s now run the script:

python tams_dw1D.py

The algorithm should run for a few seconds, depending on your platform and how fast the model transitions. The default log level will report on the algorithm progress during the entire process, and reports a final summary of the form:

####################################################

# TAMS v0.0.6 trajectory database #

# Date: 2025-11-26 14:58:21.980592+00:00 #

# Model: doublewell1D #

####################################################

# Requested # of traj: 50 #

# Requested # of splitting iter: 500 #

# Number of 'Ended' trajectories: 50 #

# Number of 'Converged' trajectories: 50 #

# Current splitting iter counter: 325 #

# Current total number of steps: 188618 #

# Transition probability: 0.0013906155192709678 #

####################################################

TAMS converged after 325 selection/mutation steps, time at which all 50 trajectories exceeded \(\xi_b\) within the 10 time units window. A total of 188618 model steps were taken and the transition probability estimate is \(\hat{P} = 1.39e^{-3}\).

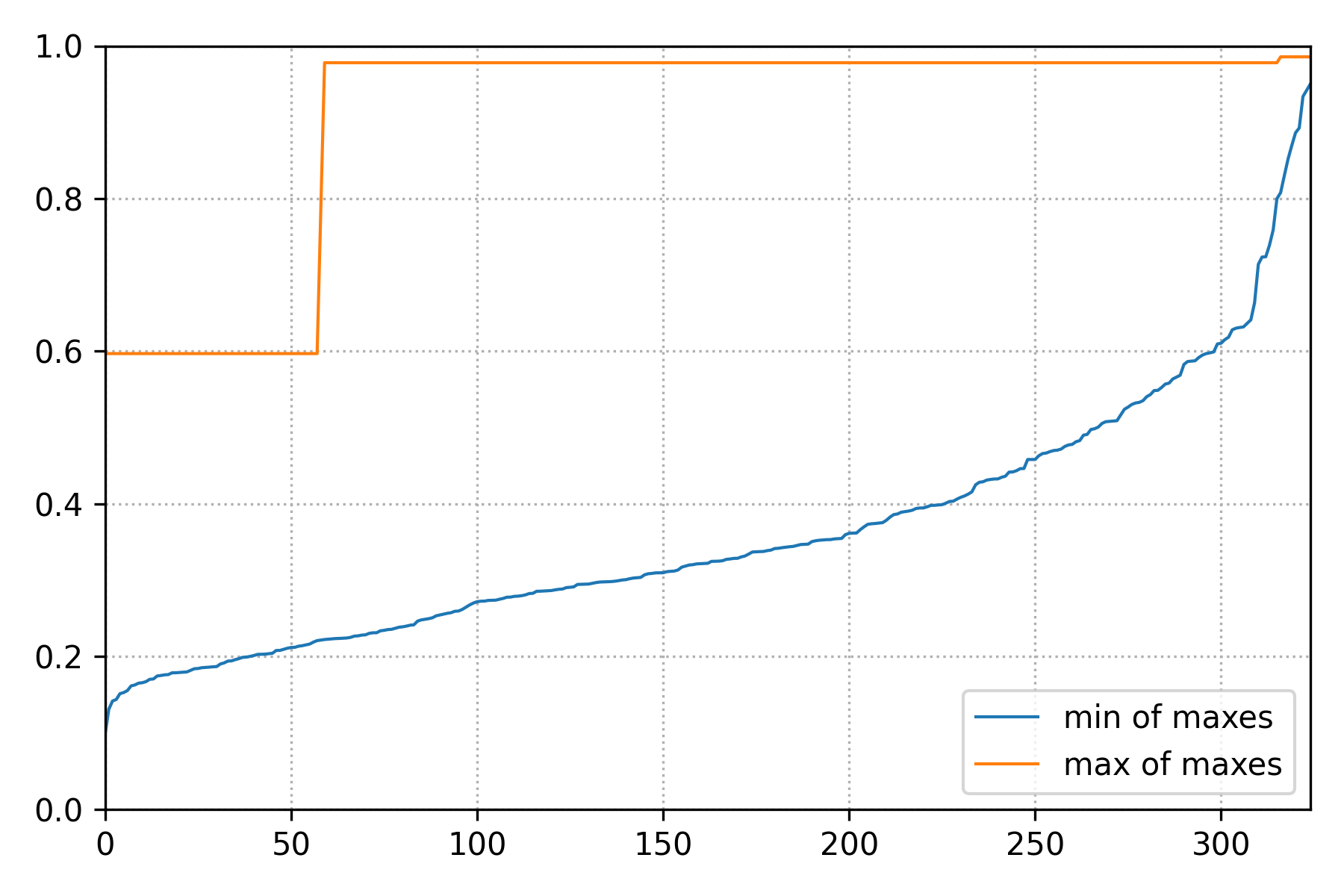

In addition, the script above access the TAMS database to show the history of the ensemble score functions span (the span of \(\mathcal{Q}_{tr}\)).

Figure 8 Span of \(\mathcal{Q}_{tr}\) over the course of the TAMS iterations.¶

We can this that in this high noise setting, one trajectory rapidly reaches \(\mathcal{B}\), but many more iterations are needed for the entire ensemble to transition.

This is all for this tutorial. We have covered the following points:

Getting pyTAMS

Going from a pen-and-paper SDE to a practical implementation ready for pyTAMS

Testing the model on a single, isolated trajectory

Running TAMS

To go further, modify the tams_dw1D.py script to run TAMS \(K\) times and

provide a better estimate of the transition probability \(\overline{P}_K\), as well as

its relative error. What happens when \(\epsilon\) is reduced? Can you trigger saving

the TAMS database to disk?

Bi-channel problem¶

In this tutorial, you will explore transitions in the bi-channel/triple wells, two-dimensional dynamical system. This system is regularly used for testing rare event algorithm, see for instance Brehier et al.. In contrast with the 1D double well tutorial, we will use the implementation already available in pyTAMS examples and focus on using the algorithm to explore the system behavior.

Background¶

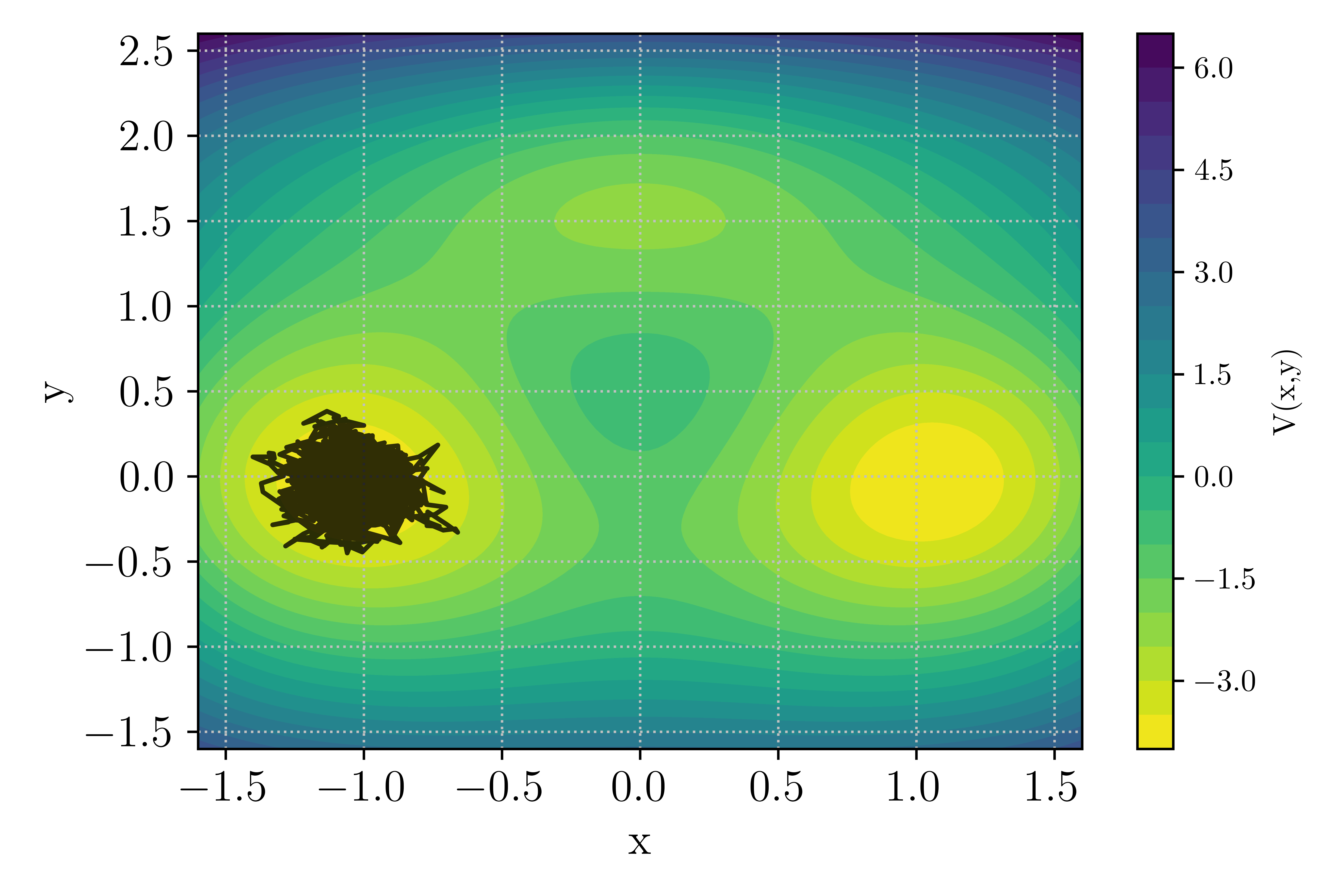

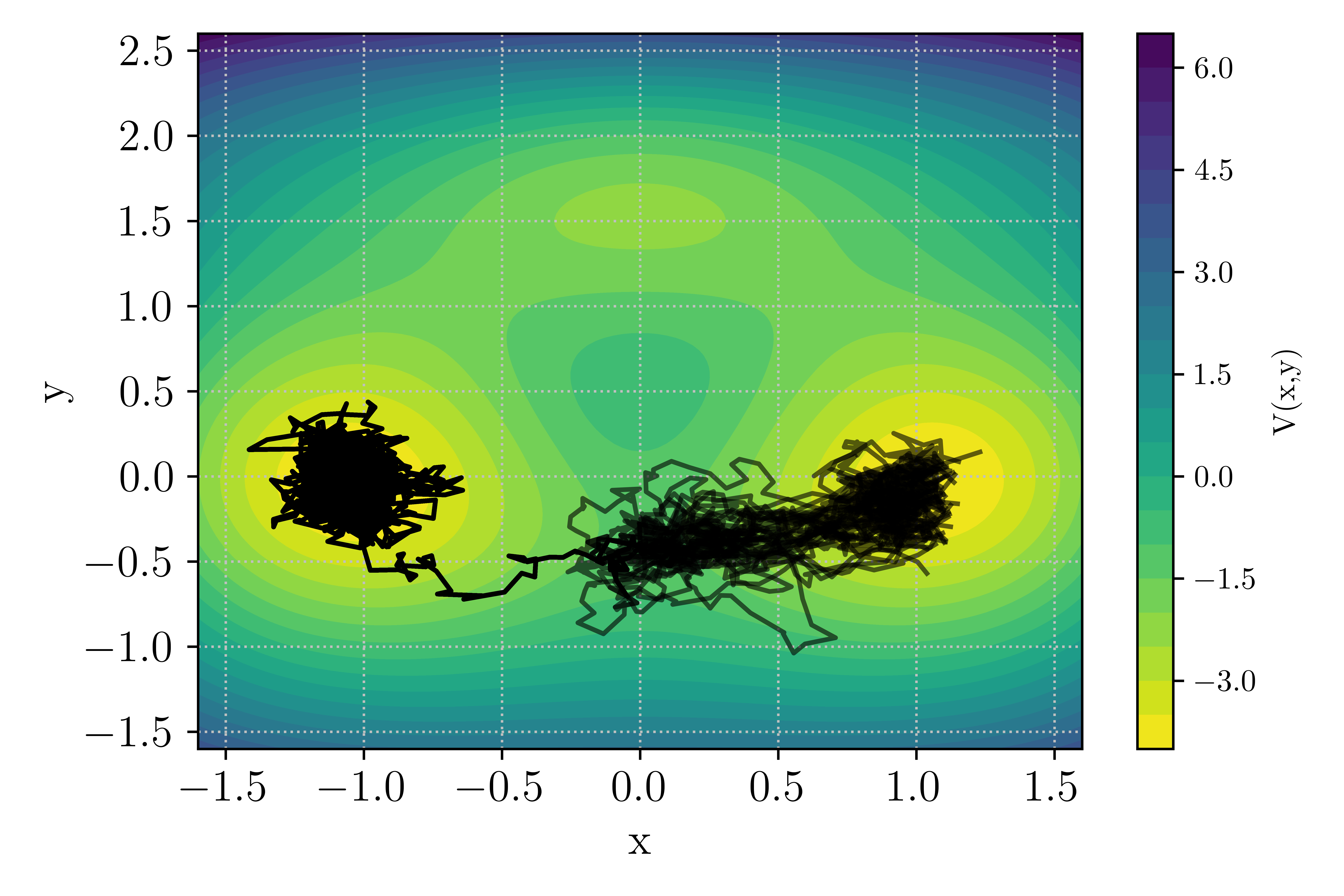

The bi-channel/triple well is a 2D overdamped diffusion process in which the potential landscape features two global minimum (at \((\pm 1.0, 0.0)\)) as well as a local minimum near \((0.0, 1.5)\). The global minima are connected by two channels: the upper channel through the local minima while the lower channel goes through the saddle point near \((0.0, -0.4)\). To take the upper channel, a trajectory will need to overcome two energy barriers to enter and exit the local minima, while the lower channel one feature a single barrier albeit of higher depth.

The potential as well as a system trajectory initiated near the left global minima \(\mathcal{A} = (x_A,y_A) = (-1,0)\) is presented in Fig. Figure 9.

Figure 9 : Potential landscape of the bi-channel/triple well 2D case.¶

The noise level in this model is set by the inverse temperature parameter \(\beta\), with low values of \(\beta\) corresponding to a high noise level. At low noise levels, the upper channel is more likely as the two smaller energy barriers are easier to cross. In contrast, at high noise levels the shorter lower path becomes more likely as strong noise is able to push the system across the saddle point.

Getting set up¶

If you haven’t done so yet, let’s get pyTAMS installed on your system. In order to have access to the example suite, you will need to install the package from sources.

git clone git@github.com:nlesc-eTAOC/pyTAMS.git

cd pyTAMS

pip install -e .

tams_check

The last line check that pyTAMS is effectively installed and should return (with proper version numbers):

== pyTAMS vX.Y.Z :: a rare-event finder tool ==

Move into the example folder

cd pyTAMS/examples/BiChannel2D

The Forward Model¶

We will not have to modify the forward model in this tutorial, but it is still interesting

to have a look at the content of the bichannel2d.py file. A quick check of the methods

defined for this model reveals that all the required @abstractmethod from the pyTAMS ABC are

provided with a concrete implementations (see Tutorial on 1D double well for more details

on this point).

In addition, a potential and drift are available to readily access the process

parameters.

def _init_model(self, m_id: int, params: dict[typing.Any, typing.Any]) -> None:

def _advance(self, step: int, time: float, dt: float, noise: Any, need_end_state: bool) -> float:

def potential(cls, x: npt.NDArray[np.number]) -> npt.NDArray[np.number]:

def drift(cls, x: npt.NDArray[np.number]) -> npt.NDArray[np.number]:

def get_current_state(self) -> Any:

def set_current_state(self, state: Any) -> None:

def score(self) -> float:

def make_noise(self) -> Any:

The state is a Numpy array with two elements and the noise dimension is also \(m=2\). The model also uses an Euler-Murayama scheme to advance in time and the score function is the normalized distance to \(\mathcal{A}\):

To test that the model is effectively available, you can reproduce Fig. Figure 9 by running the provided test script:

python test_bichannel.py

The script uses the Forward Model potential function to draw contours of \(V(x,y)\).

Running TAMS¶

Let’s now focus on running TAMS. As mentioned above, this case features two paths for transitioning

from \(\mathcal{A} = X_A = (x_A,y_A) = (-1,0)\) to \(\mathcal{B} = X_B = (x_B,y_B) = (1,0)\). We will start

with running TAMS using \(N=32\) and up to \(J=1000\) iteration. The time horizon is

set to \(T_a = 20\) and the stopping criterion delimiting \(\mathcal{B}\) is \(\xi_b = 1.05\).

All of these parameter can be set in the input.toml file:

[tams]

ntrajectories = 32

nsplititer = 1000

loglevel = "WARNING"

[trajectory]

end_time = 20.0

step_size = 0.01

targetscore = 1.05

[model]

inv_temperature = 5.67

[runner]

type = "asyncio"

nworker_init=1

nworker_iter=1

Note that the log level here was decreased to WARNING in order to minimize standard output clutering

when running TAMS multiple times. Let’s now look at the short script provided for running TAMS with the

bi-channel model tams_bichannel.py:

import numpy as np

from bichannel2d import BiChannel2D

from bichannel2d import plot_in_landscape

from pytams.tams import TAMS

if __name__ == "__main__":

# For convenience

fmodel = BiChannel2D

# Enable TAMS trajectory plots

plot_ensemble = True

# Number of consecutive TAMS runs

K = 10

# Run the model several times

for i in range(K):

# Initialize the algorithm object

tams = TAMS(fmodel_t=fmodel)

# Run TAMS and report

try:

probability = tams.compute_probability()

except RuntimeError as e:

print(e) # noqa: T201

continue

print(f"[{i}] : {probability}") # noqa: T201

if plot_ensemble:

plot_in_landscape(fmodel, tams.get_database(), i)

print(f"Averaged transition P_K: {probabilities.mean()}, RE: {np.sqrt(probabilities.var()) / probabilities.mean()}") # noqa : T201

As listed above, the script will perform \(K = 10\) consecutive TAMS runs and report on the averaged

transition probability \(P_K\) as well as the relative error. In addition, if the plot_ensemble is activated,

a figure showing the TAMS trajectory ensemble in the potential landscape will be generated for each run.

Let’s run the script:

python tams_bichannel.py

Depending on the platform you are using, it will take a few minutes to run.

Note

Some of the individual TAMS run might have terminated with:

`

Splitting is stalling with all trajectories stuck at a score_max: 0.7399799334097721

`

This is an occurrence of extinction, a known issue of (T)AMS algorithms in which the

ensemble collapse on a single ancestor trajectory and no significant progress is made

through iterations until all trajectories have the same \(Q_{tr}\). This problem

is more likely when using small ensemble or using a static score function in TAMS, as

we do here.

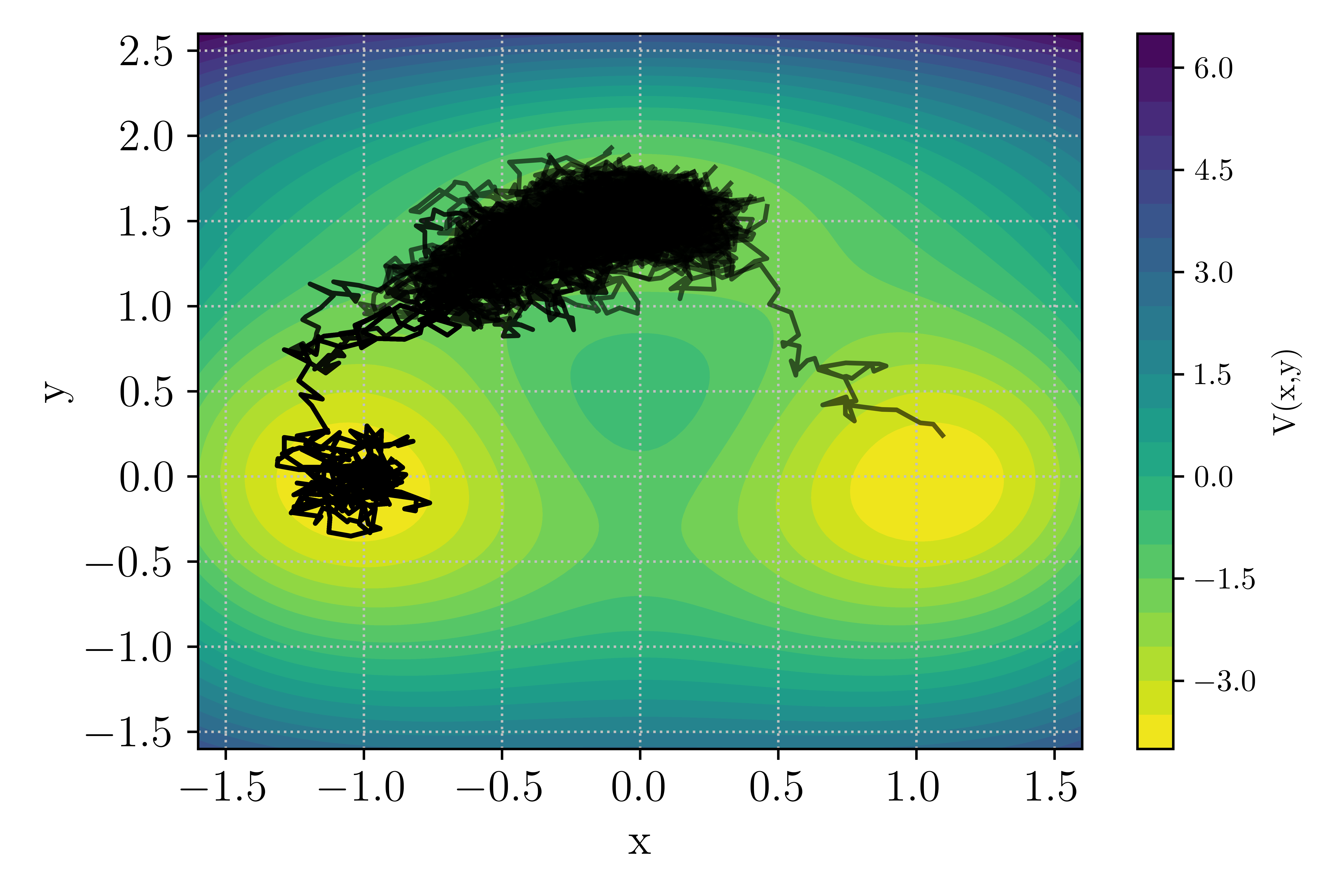

At the value of the inverse temperature set in the input file \(\beta = 5.67\), transition through both channel can occurs with a significant probability such that out of the 10 runs, you should observe both upper and lower channel transition as depicted in the figure below.

Figure 10 : Example of TAMS run with transition in the upper or lower channel¶

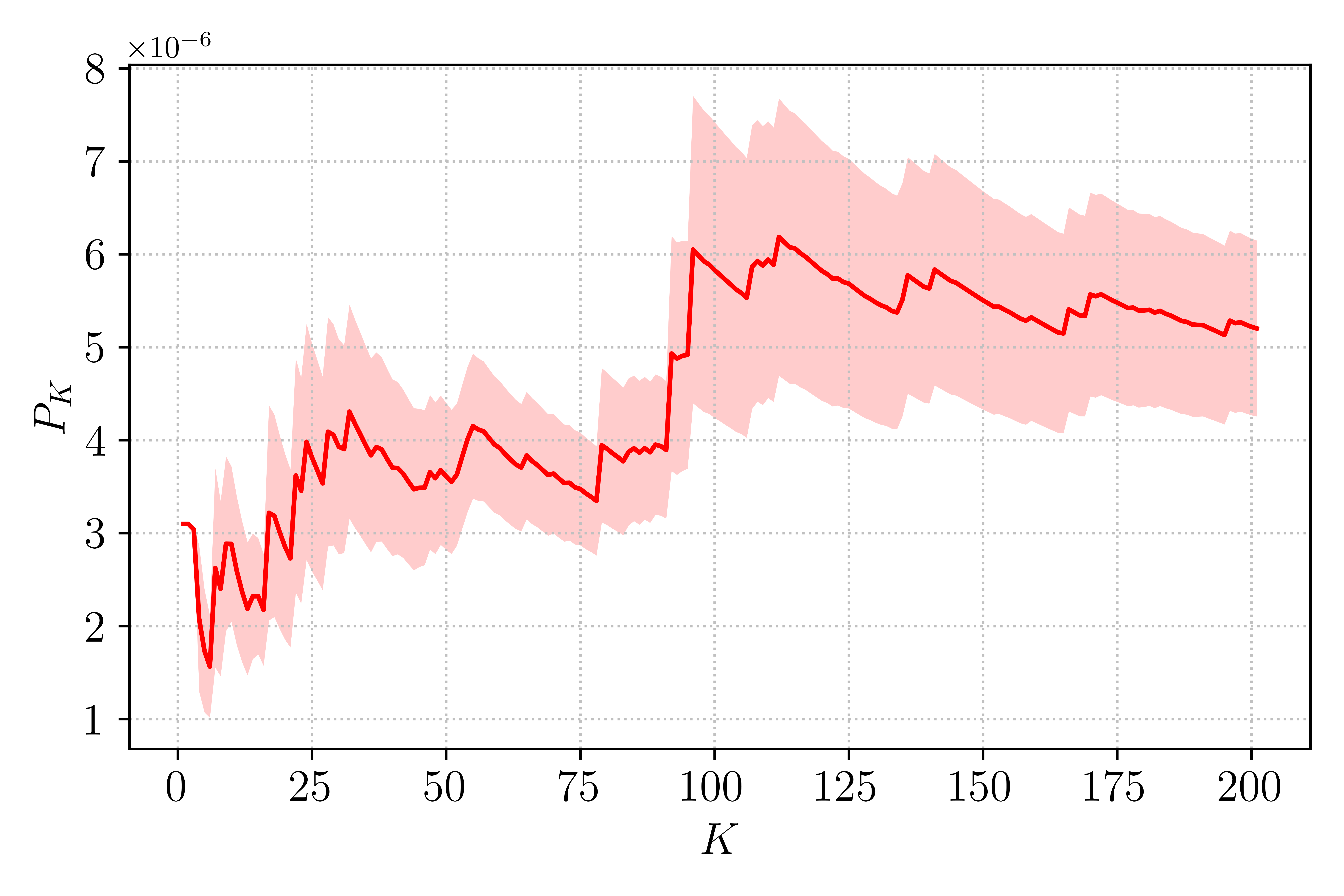

Let’s have a look at the behavior of the transition estimator \(P_K\) as \(K\) increases. This is similar to the experiment reported in Brehier et al., but we will limit the exercise to \(K = 200\). Running such an experiment would take significant time, beyond the scope of this tutorial. Instead, the probability of 200 TAMS runs are already available in the example folder and can be readily analyzed. Note that the data were generated using \(\beta = 6.67\) for which the transition probability is lower than in the earlier runs we performed here.

The data are stored in a Numpy file Pk_beta_6p67_K200.npy. We will write a small script

to load the data and plot the evolution of \(P_K\) as \(K\) goes from 1 to 200.

In a new Python file ((e.g. Pk_estimator.py):

import contextlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Load the numpy data

proba = np.load("./Pk_beta_6p67_K200.npy")

# Initialize data containers for P_K

# and the confidence interval

pbar = np.zeros(proba.shape[0] - 1)

pbar[0] = proba[0]

pbar_ci = np.zeros(proba.shape[0] - 1)

# Compute pbar and pbar_ci

for k in range(1, proba.shape[0] - 1):

pbar[k] = proba[:k].mean()

pbar_ci[k] = 1.0 / np.sqrt(k) * np.sqrt(proba[:k].var())

# Plot the results

with contextlib.suppress(Exception):

plt.rcParams.update({"text.usetex": True, "font.family": "serif"})

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 4))

plt.xticks(fontsize="x-large")

plt.yticks(fontsize="x-large")

plt.xlabel("$K$", fontsize="x-large")

plt.ylabel("$P_K$", fontsize="x-large")

plt.plot(np.linspace(1, proba.shape[0] - 1, proba.shape[0] - 1), pbar, color="r")

plt.fill_between(

np.linspace(1, proba.shape[0] - 1, proba.shape[0] - 1),

pbar - pbar_ci,

pbar + pbar_ci,

color="r",

alpha=0.2,

linewidth=0.0,

)

plt.grid(linestyle=":", color="silver")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Running the script above in the bi-channel folder should produce the graph shown in Fig. Figure 11. Over the course of 200 runs, the estimator varies significantly and even with \(K = 200\) the value of \(P_K\) continues to change. Of interest is the shaded area, showing the 90% confidence interval, which gives an indication of the transition probability estimator quality.

Figure 11 : Evolution of \(P_K\) with \(K\) repetitions of the TAMS algorithm.¶

Accessing the TAMS database¶

So far, we have performed multiple runs of TAMS but have had limited access to the welth of data generated during the course of the algorithm. Looking back into the previous section, we have used TAMS data to visualize the trajectory ensemble on the potential landscape. The TAMS database object can be accessed during or after a TAMS run using:

tdb = tams.get_database()

where tams is an instance of the TAMS object. In the example script used above, the database

object is send to the function constructing the plot: the plot_in_landscape function

in bichannel2d.py. The few lines of code used to access the data in the database are reported

below:

for t in tdb.traj_list():

state_x = np.array([s[1][0] for s in t.get_state_list()])

state_y = np.array([s[1][1] for s in t.get_state_list()])

Here we loop on the list of active trajectories tdb.traj_list(), i.e. the ensemble

of \(N\) trajectories active at the current iteration of the algorithm. We then used Python

list comprehension to go through the trajectory and extract a Numpy array of the system state

components \(x\) and \(y\).

In our previous TAMS runs, we could no longer access the database after exiting the script

since the data was not saved to disk. Let’s now run one more time the algorithm, allowing to

create a database on disk. To do so, let’s add the appropriate keyword to the input file

input.toml:

[database]

path = "./db_tams_bichannel.tdb"

,update the tams_bichannel.py script to only run once by changing the value of \(K\):

# Number of consecutive TAMS runs

K = 1

and run the script again:

python tams_bichannel.py

Note that saving the database to disk incurs an overhead, which is not negligeable for such a small model. Looking into your run folder should now show that a TAMS database was saved:

ls -d db*

db_tams_bichannel.tdb

Let’s now put together a small script to load the database and access some of its data.

In a new Python file (e.g. load_database.py):

from pytams.database import Database

from pathlib import Path

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Load the database from disk

tdb = Database.load(Path("./db_tams_bichannel.tdb"))

tdb.load_data(load_archived_trajectories=True)

# Show the ensemble scores at the last iteration

tdb.plot_score_functions("./ScoreEnsemble.png")

# Show the evolution of the ensemble span over

# the course of TAMS iterations

tdb.plot_min_max_span("./ScoreMinMax.png")

# Go through the active trajectories

# and display the max score

for t in tdb.traj_list():

print(f"Trajectory {t.id()} final max score: {t.score_max()}")

# Get the active trajectory list at initial iteration

# and display the max score

for t in tdb.get_trajectory_active_at_k(0):

print(f"Trajectory {t.id()} initial max score: {t.score_max()}")

The first line above instantiate the Database object, but only load metadata from disk. Only data such

as the number of trajectories, the current index of the TAMS iteration and some trajectories metadata

(did it converged, what is the maximum of the score function, …) are available.

The load_data function effectively load the entire content of the trajectories in memory. By default

only the active trajectory data are loaded, i.e. the trajectory at the end of the TAMS algorithm. By

activating the load_archived_trajectories flag, we trigger loading the full list of trajectories

including the ones discarded during the TAMS iterations.

A couple of helper functions allow to asses the state of the ensemble by plotting the score functions

as well as the evolution of the ensemble over the course of the iterations.

This is all for this tutorial. We have covered the following points:

Exploring one of pyTAMS built-in example

Running TAMS multiple times in order to get a better transition probability estimator and uncertainty

Accessing, saving and loading the TAMS database

To go further, modify the change the value of the inverse temperature \(\beta\) parameter

and see how that affect the probability of transitioning through the upper and lower channels,

look at the Database and Trajectory APIs (database API)

to extract more data from the database and get the most out of your TAMS runs !

2D Boussinesq model¶

So far, the tutorials have been focused on fairly simple models for which pyTAMS is practical, but also incurs a computational overhead that might not be justified compared to more simple implementation of the algorithm.

We will now turn our attention to a more complex model, with \(10^4\) degrees-of-freedom

for which pyTAMS is specifically designed for. The model is a stochastic partial

differential equation (SPDE) described in Soons et al..

Two versions of this model are available in pyTAMS examples and the present tutorial will

focus on the C++ implementation examples/BoussinesqCpp in order to demonstrate how

to couple pyTAMS with an external software (as might be the case for many user of existing

physics models). The interested reader can dig into the examples/Boussinesq to study the

implementation of a Python-only version.

One final note to motivate the use of pyTAMS: a \(10^4\) state requires about 80 kB of memory and considering a model trajectory consists of 4000 individual states, an active set of \(N=20\) trajectories requires about 6 GB of memory. This turns out to be only a fraction of the full memory requirements of TAMS as the total number of trajectories increases with the number of iterations, making it impossible to run TAMS on such a model without partially storing data to disk and sub-sampling the states (both native features of pyTAMS).

Getting set up¶

If you haven’t done so yet, let’s get pyTAMS installed on your system. In order to have access to the example suite, you will need to install the package from sources.

git clone git@github.com:nlesc-eTAOC/pyTAMS.git

cd pyTAMS

pip install -e .

tams_check

The last line check that pyTAMS is effectively installed and should return (with proper version numbers):

== pyTAMS vX.Y.Z :: a rare-event finder tool ==

Move into the example folder

cd pyTAMS/examples/BoussinesqCpp

BoussinesqCpp Folder content¶

Before diving into the code, let’s first have a look at the content of the folder as many more files are involved compared to previous tutorials:

Boussinesq.cpp # Implementation of physics model in C++

Boussinesq.h # C++ model headers

Makefile # GNUmake file

Messaging.h # Messaging library header, C++ side

OFFState.bin # Model OFF state data, in binary format

OFFState.xmf # Model OFF state data visualization (use Paraview)

ONState.bin # Model ON state data, in binary format

ONState.xmf # Model ON state data visualization (use Paraview)

README.md

__init__.py

boussinesq2d.py # The forward model implementation

eigen_lapack_interf.h # Eigen to LAPACK interface C++ header

input.toml # TAMS input file

messaging.py # Messaging library, Python side

tams_boussinesq2d.py # Script for running TAMS

There are three main components to this model:

The model physics is encapsulated in a C++ program (

Boussinesq.h,Boussinesq.cpp,eigen_lapack_interf.h)An inter-process communication (IPC) module with a C++ (

Messaging.h) and a Python (messaging.py) sideThe pyTAMS ABC concrete implementation for this model (

boussinesq2d.py)

When coupling an external model to pyTAMS, one should consider the possibility of maintaining the physics program continuously running in the background to avoid having to start and terminate the program repeatedly. In the present case, we implemented a simple IPC that enables running the C++ in the background all the time while controlling its flow from Python as pyTAMS proceeds. This might not always be possible if you do not have access to the physics program source code.

Our aim here is not to dive too much into the C++ side, as the physics implementation is not particularly transferable to other cases, but to explore how to set up the ABC forward model implementation for an external program.

Let’s kick off this tutorial by compiling the physics program.

Follow the instructions of the README.md file to obtain the external dependencies for this

case (Eigen and LAPACK) and make sure you are able to compile the C++ program:

make

ls boussinesq.exe

BoussinesqCpp forward model¶

Let’s first look at the _init_model function in boussinesq2d.py to get a clear view of the

model attributes:

self._m_id = m_id # The unique id of the model instance

self._M = subparms.get("size_M", 40) # Number of grid point in latitude

self._N = subparms.get("size_N", 80) # Number of grid point in depth

self._K = subparms.get("K", 7) # Number of Fourier modes for the stochastic forcing

self._eps = subparms.get("epsilon", 0.05) # Variance of the Wiener noise process

self._exec = subparms.get("exec", None) # The executable of the external physics program

self._exec_cmd = [ # The command to start the external physics program

self._exec,

"-M",

str(self._M),

"-N",

str(self._N),

"-K",

str(self._K),

"--eps",

str(self._eps),

"--pipe_id",

str(m_id),

]

self._proc = None # The id of the process of the external program

self._pipe = None # The IPC (named here pipe as it uses two-way pipes)

self._state = subparms.get("init_state", None) # The model state

The model physical parameters are read from the input file (size_M, size_N, K, epsilon) and used

to start the external program along with a path to its executable. The C++ program does not start at this point,

but will be launched upon calling the advance function for the first time.

In this model, the state is not directly the model state as an array of data but rather a path to

a file on disk, generated/read by the external model. This has direct implication for the setter and getter

function of the ABC: the set_current_state function must not only set the self._state variable on the

Python side, but also communicate that information with the C++ program:

def set_current_state(self, state: Any) -> None:

"""Set the model state.

And transfer it to the C++ process if opened

Args:

state: the new state

"""

self._state = state

if not self._proc:

return

self._pipe.post_message(Message(MessageType.SETSTATE, data=state.encode("utf-8")))

ret = self._pipe.get_message()

if ret.mtype != MessageType.DONE:

err_msg = "Unable to set the state of the C++ code"

_logger.error(err_msg)

raise RuntimeError

If we now take a closer look at the advance function, there are a few notable things to notice:

def _advance(self, _step: int, _time: float, dt: float, noise: Any, need_end_state: bool) -> float:

"""Advance the model.

Args:

step: the current step counter

time: the starting time of the advance call

dt: the time step size over which to advance

noise: the noise to be used in the model step

need_end_state: whether the step end state is needed

Return:

Some model will not do exactly dt (e.g. sub-stepping) return the actual dt

"""

if not self._proc:

# Initialize the C++ process and the twoway pipe

self._proc = subprocess.Popen(self._exec_cmd)

self._pipe = TwoWayPipe(str(self._m_id))

self._pipe.open()

# Send the workdir

self._pipe.post_message(Message(MessageType.SETWORKDIR, data=self._workdir.as_posix().encode("utf-8")))

# Set the initial state

self.set_current_state(self._state)

if need_end_state:

self._pipe.post_message(trigger_save_msg)

self._pipe.post_message(Message(MessageType.ONESTOCHSTEP, data=noise.tobytes()))

ret = self._pipe.get_message()

if ret.mtype != MessageType.DONE:

err_msg = "Unable to access the score from the C++ code"

_logger.error(err_msg)

raise RuntimeError

self._score = struct.unpack("d", ret.data)[0]

if need_end_state:

self._state = self.get_last_statefile()

else:

self._state = None

return dt

Upon the first call to the advance function, the C++ program is started using Python subprocess. At the same time, the IPC two-way pipe is initialized and the initial condition communicated to the external program.

pyTAMS’s trajectory API allows to downsample the state stored in the trajectory and the advance function

need_end_stateargument is set toTruewhen the algorithm expects a state. This is also transferred to the C++ program before effectively advancing the model. Depending on how your model handles IO, you can use this parameter to make sure a checkpoint file is generated (or possibly suppress a checkpoint file if your model always produces IO but it is not needed)

The noise increment for the model’s stochastic forcing is still generated on the Python side and communicated to the external C++ program when performing a model time step. Additionally, the Python ABC does not have access to the C++ program state variables (i.e. the physical field of temperature, salinity, …) and must query the model to get the score function (transferring entire variable fields to Python would slow the model significantly).

One last function worth noting is _clear_model:

def _clear_model(self) -> None:

if self._proc:

self._pipe.post_message(exit_msg)

self._proc.wait()

self._proc = None

self._pipe.close()

self._pipe = None

This function is part of pyTAMS forward model ABC but does not need to be overwritten by a concrete implementation. It is always called upon completing a trajectory (i.e. reaching the score function target value or the final time horizon) and in the current model, it terminates the external C++ program.

Running TAMS locally¶

We will now run TAMS with the Boussinesq model. This model is significantly more computationally expensive that the other models used in previous tutorial, but it still only takes a few dozens minutes to perform a TAMS run on a laptop.

Let’s review the content of the input file input.toml:

[tams]

ntrajectories = 20

nsplititer = 200

loglevel = "INFO"

diagnostics = true

The number of ensemble member is set to \(N=20\) and the maximum of iteration set to \(J = 200\).

We enable diagnostic to True is order to visualize the evolution of the ensemble during the course

of the iterations, as depicted in the last graph of the Theory Section.

[trajectory]

end_time = 20.0

step_size = 0.005

targetscore = 0.95

sparse_freq = 10

The time horizon is set to \(T_a = 20\) time units and the step size 0.005. The target score function

defining the model AMOC collapsed state is \(\xi_b = 0.95\). Finally, only one state every 10 steps will

be requested (i.e. the advance function argument need_end_state will be False 9 out of 10 calls. This

reduce by an order of magnitude the disk space requirements. Note that this parameter is a disk space versus

compute trade-off, as sparser trajectory will require to recompute some model steps during the cloning/branching

step of the algorithm.

[model]

exec = "./boussinesq.exe"

init_state = "./ONState.bin"

size_M = 40

size_N = 80

epsilon = 0.05

K = 7

The model parameters are parsed in the model _init_model function and control the size of computational

model as well as stochastic forcing shape and intensity. The initial condition is set to be the AMOC ON state.

Note that the noise level here is fairly high \(\epsilon = 0.05\), such that the transition is not so rare

in order to limit the compute time.

[runner]

type = "dask"

nworker_init=2

nworker_iter=2

When running the model locally, both asyncio and dask runner are valid options. Here we use Dask by default, spawning two workers during the initial ensemble generation and two workers during the TAMS iterations. The later parameter effectively means that at least the two trajectories with the lowest value of the maximum score function will be discarded and new trajectory cloned/branched at each TAMS iterations.

[database]

path = "2DBoussinesqCpp.tdb"

Running this model always requires creating a database on disk to store the external model data.

As with previous Tutorials, there a short script in the example folder to launch TAMS:

python tams_boussinesq2d.py

For the sake of keeping this tutorial short, only a single TAMS run is required.

The standard output should look something like:

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:46:02,769 -

####################################################

# TAMS v0.0.6 trajectory database #

# Date: 2025-12-04 21:46:02.752567+00:00 #

# Model: 2DBoussinesqModelCpp #

####################################################

# Requested # of traj: 20 #

# Requested # of splitting iter: 500 #

# Number of 'Ended' trajectories: 0 #

# Number of 'Converged' trajectories: 0 #

# Current splitting iter counter: 0 #

# Current total number of steps: 0 #

# Transition probability: 0.0 #

####################################################

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:46:02,785 - Computing 2DBoussinesqModelCpp rare event probability using TAMS

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:46:02,785 - Creating the initial ensemble of 20 trajectories

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:46:03,292 - Advancing traj000002_0000 [time left: 86399.487147]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:46:03,293 - Advancing traj000003_0000 [time left: 86399.486938]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:46:28,092 - Advancing traj000018_0000 [time left: 86374.679952]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:46:28,120 - Advancing traj000006_0000 [time left: 86374.651914]

...

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:50:49,663 - Advancing traj000010_0000 [time left: 86113.108818]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:51:14,384 - Advancing traj000012_0000 [time left: 86088.387617]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:51:14,437 - Advancing traj000000_0000 [time left: 86088.334118]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:51:39,418 - Run time: 336.648924 s

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:51:39,418 - Using multi-level splitting to get the probability

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:51:39,992 - Starting TAMS iter. 0 with 2 workers

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:51:40,595 - Restarting [19] from traj000003_0000 [time left: 86062.184477]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:51:40,597 - Restarting [4] from traj000001_0000 [time left: 86062.183612]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:52:02,934 - Starting TAMS iter. 2 with 2 workers

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:52:03,365 - Restarting [10] from traj000019_0001 [time left: 86039.406361]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:52:03,383 - Restarting [2] from traj000017_0000 [time left: 86039.388611]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:52:23,398 - Starting TAMS iter. 4 with 2 workers

...

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:59:55,533 - Starting TAMS iter. 102 with 2 workers

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:59:55,848 - Restarting [8] from traj000016_0008 [time left: 85566.924079]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:59:55,879 - Restarting [7] from traj000000_0003 [time left: 85566.892251]

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:59:57,955 - Starting TAMS iter. 104 with 2 workers

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:59:58,134 - All trajectories converged after 104 splitting iterations

[INFO] 2025-12-04 22:59:58,317 - Run time: 835.547348 s

[INFO] 2025-12-04 23:00:02,499 - 104 archived trajectories loaded

[INFO] 2025-12-04 23:00:02,521 -

####################################################

# TAMS v0.0.6 trajectory database #

# Date: 2025-12-04 21:46:02.752567+00:00 #

# Model: 2DBoussinesqModelCpp #

####################################################

# Requested # of traj: 20 #

# Requested # of splitting iter: 500 #

# Number of 'Ended' trajectories: 20 #

# Number of 'Converged' trajectories: 20 #

# Current splitting iter counter: 106 #

# Current total number of steps: 183619 #

# Transition probability: 0.0037570973859534823 #

####################################################

Since diagnostic is set to True, a series of images Score_k0****.png showing the

ensemble at each iterations (every two cloning/branching events) is generated.

Running TAMS on a Slurm cluster¶

In the event you have access to an HPC cluster, we will now update the input file to run TAMS on a Slurm cluster.

[tams]

walltime = 7100

[dask]

backend = "slurm"

worker_walltime = "2:00:00"

queue = "genoa"

ntasks_per_job = 1

job_prologue = ['module load Python', 'conda activate pyTAMS']

The default backend of the dask runner is local, by setting it to slurm Dask will

submit the workers as Slurm jobs. The job wall time will be set to 2 hours and be submitted to

the genoa partition. The algorithm walltime must thus be updated to not exceed the job wall time.

The strings listed in the job_prologue will be executed before starting the worker and can be

used to setup your environment.

If your cluster allows it, can launch the TAMS script from the login node (very to no compute is done by the main process in TAMS), otherwise you will have to launch the TAMS script from a Slurm batch script.

This is all for this tutorial. We have covered the following points:

Interfacing an external program with pyTAMS

Triggering diagnostics while running TAMS

Using multiple workers and running TAMS on a Slurm cluster

To go further, interested users can change the model noise parameters or repeat the experiment multiple times. Additionally, the Python version of the Boussinesq model has several custom features and comparing the two implementations could be a good source of information for developing your own model.